Water quality in Chicago's rivers improving, but still needs work

Credit: Shanthanu Bhardwaj

Most folks in Chicago think of an afternoon picnic, a leisurely stroll or a day of fishing as lakefront, rather than riverfront, activities.

When talking about the rivers with your neighbor or coworkers, you’re likely to encounter a perception that they are polluted and not attractive or pleasant to visit. While there is a growing community that frequents the rivers—from kayakers and rowers to birders and naturalists—many of Chicagoland’s residents continue to look outside the city for interaction with natural assets.

In spite of this negative perception, there is great potential in our river system. When Great Rivers Chicago surveyed more than 3,700 local residents and business owners, we found overwhelming agreement that our rivers should be cleaner, healthier places—not only for people but also for plants and animals. Improved water quality will be a key part of the Great Rivers Chicago vision to make our waterways a place where people will want to spend time.

You’ve got to admit it’s getting better

Chicago’s waterway system is a combination of natural and channelized rivers. Each segment has a unique character and hosts dramatically different uses. From residential in the north to manufacturing in the south, the system has been contending with a range of point and non-point source pollution over the years. Bubbly Creek on the South Branch of the Chicago River has been the dumping ground for livestock entrails from the city’s once-booming meat-packing industry, while the North Shore Channel has been battling combined sewer overflow events and foul odors wafting from nearby wastewater treatment plants. The upper Des Plaines River—a slow, low-lying river that meanders through woodlands on the city’s northwestern border—historically floods and contributes to poor water quality downstream with increased build-up of fine sediment from urban runoff. The Calumet River, along with the lower North Branch of the Chicago River, has been polluted from heavy industry and continues to wrestle with the aftermath of these past and ongoing river uses.

Regardless of this variation in uses and history, the whole river system could benefit from being a lot cleaner. Chicago was one of the first cities to implement a combined sewer system—stormwater and wastewater running through the same pipes—and now with more than 200 outfalls dispersed along its river system, combined sewer overflows are an outstanding issue that affect that entire system.

That said, while our rivers have a long history of pollution problems, there have been drastic improvements in water quality and ecological health in recent years. One of the simplest indicators of water quality is the diversity of life a river can support. In 1974 there were only 10 types of fish living in the river system. By 2006, that count had increased sevenfold.

This increase in fish species over time is partially due to water quality improvement technologies. The use of chlorine to disinfect wastewater ended in 1984, reducing toxins downstream of discharge outfalls. The Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) was adopted in 1972 to control pollution and the first completed sections went into operation in 1985. By 1994, Sidestream Elevated Pool Aeration (SEPA) stations were improving water quality by adding oxygen to the water, removing odors and enhancing aquatic life.

The rivers can be home to more than just fish. In 2004, biologists began seeing river otters and muskrats along the banks of the Chicago River. Even today, these furry creatures have made a home right in the heart of Chicago’s urban canyon.

Improved water quality has brought an increase in recreational use as well. Watersports such as kayaking and boating have been attracting tourists and locals alike, bringing a new life and value to our rivers.

John Quail, director of watershed planning at Friends of the Chicago River, pointed out that “there are many different types of people using the river, and layering on top of that kayaking businesses along the river have seen a significant growth in their revenue overtime.” Quail also highlighted that the “clamor for a safety plan for the waterway is a big indicator that water quality is improving. Previously, this had not been a precedent issue, but has definitely been picking up steam over the last year.”

To maintain this trend and fully capitalize on the potential of our rivers, we’ll need to ensure our rivers continue to get cleaner, healthier and safer. We’ll also have to regularly measure their cleanliness and make those measurements easily accessible to the public.

How do we measure water quality?

As a nation, we inventory water quality and set standards to regulate surface water pollution for human and ecosystem health under the Clean Water Act (enacted in 1948 and later amended in 1972). The Ill. Environmental Protection Agency operates various water monitoring programs required by the Act to annually survey the chemical, physical, biological, habitat and toxicity data for the state’s surface and groundwater resources.

All of this data informs standards for water quality that are set by the Ill. Pollution Control Board, a sister agency to Ill. Environmental Protection Agency. These standards indicate if water is suitable for “primary contact recreational uses,” or full-body water contact like swimming and water-skiing, versus water restricted to “incidental contact recreational uses” like boating or rowing. Standards for the Chicago area were strengthened in 2012 to require many river segments to be safe for full-body contact. This higher standard is both a reflection of past water quality accomplishments and a requirement to continue making our rivers safer and healthier.

Chicagoland waterways in particular have been monitored for water quality since 1970 by the Environmental Protection Agency as well as the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago, which is responsible for treating wastewater and managing stormwater in Cook County. The District takes water samples around the Chicago waterway system from 112 sampling stations and 28 surface water “grab” locations at a monthly or sometimes weekly frequency. Every day, at least one of the three principal river systems—Chicago, Calumet or Des Plaines—is sampled.

In 2013, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District measured and analyzed 52 parameters for water quality to produce this 151-page report. They assessed both water composition and conditions to determine whether or not a healthy balance is present for supporting aquatic life and protecting human health. Water composition measurements included pollutants (metals, oils, pesticides) as well as naturally occurring components (dissolved oxygen, which is critical for maintaining aquatic organisms, bacteria and nutrients). Physical conditions of water (temperature, acidity, turbidity and sedimentary quality) are also sampled, analyzed and published in annual summary reports issued by the District.

Water quality measurements made easy

Even though we have a comprehensive process for collecting and analyzing water quality and designating what activities are safe, the information is static—not a current representation of actual conditions—perhaps outdated, and it’s not in a user-friendly format.

Allen LaPointe, vice president of environmental quality at Shedd Aquarium, pointed out that despite the comprehensiveness of the water quality measuring, “coliform is not necessarily the best measure of water quality—it’s based on old science, and yet it still seems to be a common measure.”

Although water quality information is accessible on public websites, it’s complex: Even the summary reports are difficult to digest, and real-time information is hard to come by. You can’t easily determine, for instance, if today is a good day to be kayaking on the Chicago, Calumet or Des Plaines River. Friends of the Chicago River would like to see monitoring updated to a 24-hour system; however, they acknowledge that it is very expensive.

Map of sewage outfalls during big storms

Data source: SSMMA Combined Sewer Overflow

According to Quail, “We would be able to see illicit discharges into the system [with this kind of system]. Right now we could be getting back-flow releases and purposeful discharges during storms or in the middle of the night when no one is checking water quality. You cannot catch polluters who do this with current monitoring practices, but it’s much easier with real-time monitoring.”

Real-time monitoring data, including alerts and advisories, is easily accessible for 1,800 beaches in the Great Lakes region. What would it take for us to have this level of real-time data monitoring for our rivers? The closest we come today is a website that displays whether raw sewage is potentially overflowing into the Chicago River, though even this is an educated guess, as there are no flow monitors on our sewer outfalls. (This happens as a “last resort” during heavy rainfall when sewers become overwhelmed.) Perhaps with better coordination and combining available technology with the robust monitoring we already perform, it could be possible to share easy-to-understand, up-to-date water quality information about our rivers.

“There are a lot of agencies right now looking at different aspects of water quality,” says Quail. “There could be more coordination and communication across these entities, and along these same lines more coordination across different monitoring practices.”

Protecting flora and fauna

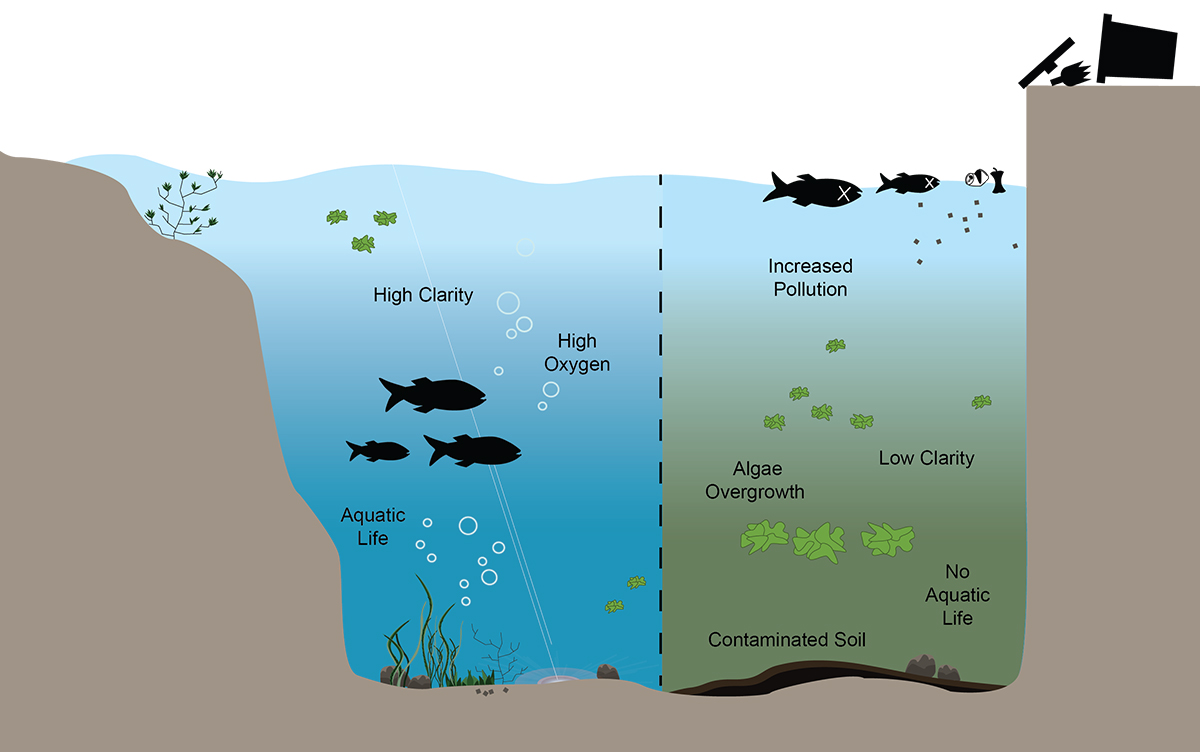

Water quality is about more than just protecting people boating on the surface; it’s about fostering diverse, healthy ecosystems that support our region’s native plant and wildlife populations. In many ways, our rivers are in dire need of habitat restoration. A group of experts convened by Chicago Wilderness concluded that habitat loss resulting from channelization, development and pollution have severely degraded the health of the wildlife and plant communities that reside within and along our waterways.

LaPointe points out that, “Clean water will not restore habitat; finding side channels to enhance vegetation and break up the [river] walls will be instrumental in restoring habitat within an altered hydrology.”

Friends of the Chicago River is contributing to habitat restoration by implementing innovative projects based on their original “fish hotel” concept, including using permeable concrete to recreate native catfish nesting cavities. The group has even created habitat within the concrete walls of Chicago’s downtown Riverwalk expansion aimed at providing habitat for native fish. Another group called the Naru Project has a vision to create a kayak park comprised of floating islands of wildlife habitats along an unnavigable strip of Chicago River’s North Branch. A group of design consultants created renderings of what Bubbly Creek might look like in the future. As part of Great Rivers Chicago, we’ll identify more areas like these for targeted habitat restoration.

Healthy plant life can play a key role in improved water quality. Plants that are native to Chicago’s region typically have long, complex root systems and can help reduce shoreline erosion by anchoring soils and reducing wave action. They also help soak up stormwater runoff and filter pollutants before reaching our rivers. Even vegetation beneath the water can improve water quality by increasing oxygen for aquatic life and taking in phosphorous loads that contribute to unwanted algae growth.

Great Rivers Chicago is bringing multiple agencies and stakeholders together to develop a vision and action agenda for Chicago’s rivers and riverfronts, including water quality. As we continue to improve our rivers’ cleanliness, they can become recreational and natural assets on par with our lakefront—places everyone can enjoy.

« Back to stories