Chance of pig entrails in Chicago's rivers today: Low

August 19, 2015

, By MPC Manager Danielle Gallet and Research Assistant Kelli-Ann Sottile

Bubbly Creek was once used as an industrial dumping ground.

When you look at the river, what is the first thing that comes to mind? Is it the green glow of St. Patrick’s Day? Or maybe the architectural boat tours that highlight our magnificent built environment? Or is it the remnants of the stock yard that plague the picture? Despite our unique answers, we all have a perception of the river deeply rooted in the city’s traditions and history.

From the very beginning of its founding in the late 1700s, Chicago has owed its existence to the river as a means of trade. The completion of the Illinois-Michigan Canal in the early 1800s further allowed for a direct trade link between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. Combined with the advent of the railroads, populations in the city grew exponentially alongside the growth of industry. By Christmas of 1865, “The Yards” were opened, propelling the city into the next stage of its history.

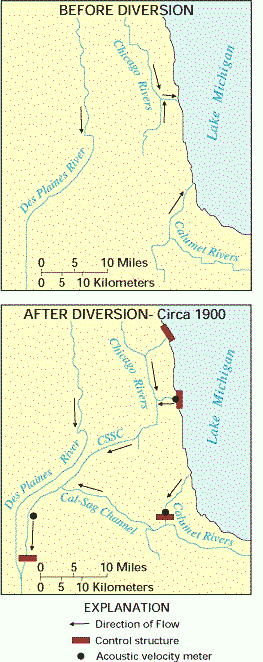

The Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC) connects the Chicago River to the Cal-Sag Channel.

Throughout this period of growth, the river became a dumping ground for not only human and industrial waste but also animal entrails left over from the stockyards. This waste then slugged its way down the river into Lake Michigan—the city’s drinking water. Not surprisingly, waterborne illnesses including cholera and typhoid raged through the city as a result in the latter half of the 19th century. For this reason, the 28-mile Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was built and famously reversed the flow of the Chicago River, carrying away all the city’s waste at the start of the new century.

With the official closure of the Union Stock Yards in 1971, this chapter in our city’s history seemed to close for good, opening the way for a brighter future. For sure today no one would ever consider it necessary to get a typhoid vaccination to visit Chicago. Yet I have to wonder, why do we still look at the river like the stockyards are alive and well?

Over the past several decades since the yard saw its end, the Water Quality Index for the Chicago River has shown a steady increase in cleanliness, and particularly in what experts refer to as “Biochemical Oxygen Demand,” which had an index score of 93 out of 100 in 2010. Biochemical Oxygen Demand is a measure of the amount of oxygen being consumed by microorganisms during the decomposition of matter in the river. This is an important factor to consider in the overall cleanliness as it indicates the amount of dissolved oxygen available in the water, which if too low will not support aquatic life. The number of unique fish species in the Chicago and Calumet Rivers has also shot up—with only 10 in 1974 and then the count reaching 70 in 2006. Life in and around the river though does not end there. Today, a variety of turtles and frogs, hundreds of species of birds and even otters and mink are among the growing list of wildlife that call the river home.

Great Rivers Chicago is a partnership between the City of Chicago, Metropolitan Planning Council, Friends of the Chicago River and others to develop a long-term, corrdinated vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers in the city. We're excited to both educate and learn from residents about the rivers and what they should look like in the future.

While we certainly do still have a ways to go in cleaning up our river from its murky past, we need to remind ourselves how far the river system and the City of Chicago has actually come over the past couple centuries and just a few decades. Maybe it is time to close the history book for a moment so we can celebrate the present and look to the potential of the future.